Overcoming Stigma to Become an Advocate for Kids with Cancer in Uganda and Beyond

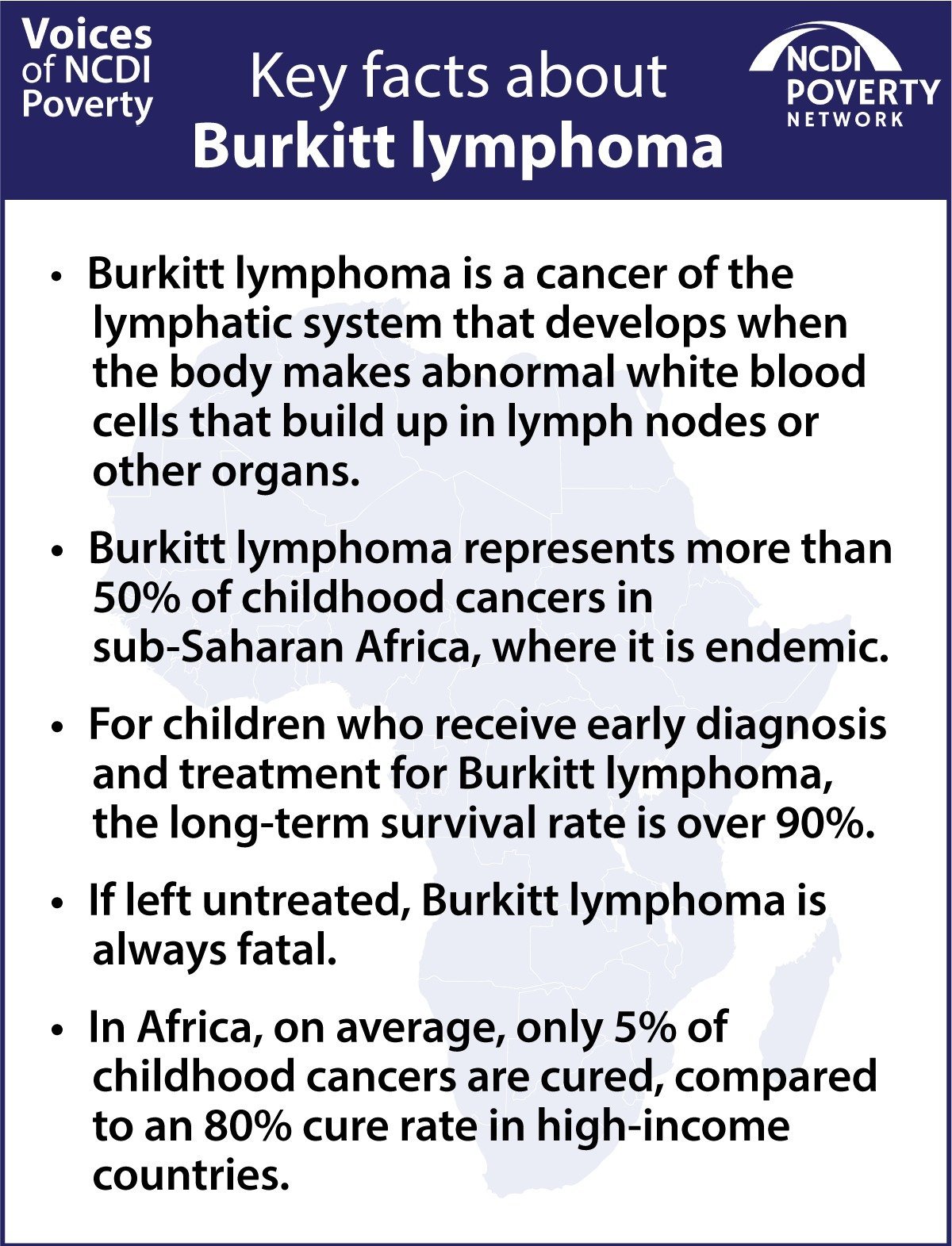

Voices of NCDI Poverty Advocacy Fellow* Moses Echodu was nine years old in 1999 when he started suffering from headaches, fatigue, fevers, and loss of appetite. His mother, who was a single mom and student at the time, realized her formerly active son who loved playing soccer with friends needed to see a doctor. But she and Moses were stunned when he was diagnosed with Burkitt lymphoma, a fast-growing cancer that is most common in children.

Echodu is quick to express gratitude for his access to medical care. Because of financial support from his extended family and free trial drugs, his mother was able to make ends meet during his treatment. But Moses’s journey wasn’t easy. The childhood cancer advocate recalls the deep sense of dismay he felt as a boy receiving inpatient treatment: As other patients inevitably passed away, young Moses experienced anxiety over his uncertain future.

In addition to the physical discomfort of receiving cancer treatment, Echodu also experienced stigma from friends, classmates, and adults in the community. After recovery, he was reluctant to disclose his experience with cancer to anyone except a few close friends. At a camp for cancer survivors in 2012, he realized that by not sharing his story, he was hiding his true self.

Now, 23 years later, Echodu is a Programs Director for the Uganda Child Cancer Foundation and has a voting role in the governance of the NCDI Poverty Network as a Voices of NCDI Poverty Advocacy Fellow. In this article, he shares his experience with childhood cancer to advocate for equitable access to cancer care and an end to stigma around the disease.

By Moses Echodu

When I was diagnosed with Burkitt lymphoma, my mom and I were shocked. Cancer was completely new to us, and the rest of my family didn’t know much about cancer either. Shock became panic as my mom started reading about cancer and doing research to try to figure out what would happen to me.

My mom was determined to make sure that I had the treatment I needed, despite the barriers to care, like stigma and cost. People told my mom not to bother paying for my cancer treatment because they didn’t think I’d survive, but the doctor encouraged her to pursue treatment options for me. I received radiotherapy and chemotherapy over the course of one year, and I was also put on a free trial drug that was in the final stages of development for Burkitt lymphoma.

During inpatient treatment I leaned on my family and my doctors for support. On days that I felt nauseous and physically weak from the treatment, the doctors assured me that I was getting better and my symptoms were normal side effects from treatment. I needed that reassurance, because not everyone makes it out of the cancer ward, and I often wondered if I would be next.

The knowledge that not every child in the cancer ward would survive was especially hard on my mom, so she relied on faith. My aunts and uncles would often bring my cousins to the hospital, and we would pray and play together. Praying with my family and playing board games with my cousins helped me feel comfortable in an unfamiliar situation. Prayer is a strong thing. It helped me feel at peace and gave me the feeling that everything would end up okay.

Meeting the challenges of cost and stigma

Echodu received inpatient treatment for Burkitt lymphoma in Uganda in 1999.

My family played a critical role in my receiving treatment. My mom was a student then, so she would spend nights with me at the hospital and rush off to school in the morning. My aunties and uncles would visit me during the day so I wouldn’t be alone. My mom was a single mom, so getting the money for treatment on top of rent, transportation, and food costs wasn’t easy. My extended family stepped up to help. My aunties and uncles found ways to contribute so the cost wasn’t an insurmountable challenge. My uncles gave my mom money for treatment and my aunt who is a doctor was able to help us access other medicines, like antibiotics and painkillers. If it wasn’t for help from my extended family and receiving trial drugs for free, we would have gone into debt during my treatment. And it shouldn’t be this way.

In 1999, when I was diagnosed, cancer was alien to most people in Uganda, and those who knew about it associated it with death. During my treatment, other kids were afraid to play with me. The adults in my community were the biggest contributors to the cancer stigma because they told their kids that they would get cancer from playing with me. The stigma is especially bad in low-income countries because treatment for cancer and other NCDs is often inaccessible and unaffordable, so people assume you will die.

I had one friend, Juma, who played a huge role in fighting stigma about my disease. He continued to play with me after everyone else shunned me out of fear. When kids would bully me, he would tell them off, then reassure me to not worry about them. There were times when I would want to play football with the other kids and they would refuse me and I would feel bad, then I would walk away in tears. When other kids refused to play with me, he would say, “If you’re not letting him play, I’m not playing.” He was great at football, and because they wanted him on their team, they would let me play too. Juma proved that people who aren’t living with NCDs can also fight stigma.

My first week back at school after completing treatment was filled with kids not wanting to sit with me or play with me, or associate with me at all. It really bothered me. But Juma helped me again. He would go out of his way to sit with me and talk to me. Eventually the other students started picking up on Juma’s actions and associating with me again. Because of Juma’s presence, I became comfortable. Some teachers also stigmatized me, but along the way they realized that I was a normal child and they had to treat me like a normal child, rather than contributing to the discrimination.

After I was declared cancer-free, I hid my cancer story from my classmates and friends because of the pain I experienced due to stigma. I became very reserved and getting to know me was difficult because I was afraid of rejection. When people living with NCDs (PLWNCDs) feel stigmatized, they become self-conscious, and they grow to expect and fear rejection. You’re already fighting a disease that’s negatively affecting your life, and the last thing you want is to feel rejected by friends, family, or people who don’t know you yet. I want to encourage both people living with and without NCDs to push back against stigma.

Finding my voice to combat stigma and advocate for access to care

Moses Echodu pictured with his mother, Salome Opus Sally.

When I was at a survivors’ camp organized by the Uganda Cancer Institute 12 years later, I finally realized that by hiding my cancer story, I was hiding myself. What’s more, people knew so little about cancer that I understood the value of sharing my survival story. For everyone who is brave enough to share their story, someone will get screened, or notice described symptoms in a child. This helps catch cancer cases early and increase survival rates.

In 2014 I reconnected with Dr. Jackson Orem, who treated my childhood cancer. He was so glad to see me grown and healthy 15 years later, and relieved to know that I was willing to share my story with the world. He connected me with the Uganda Child Cancer Foundation, and I have worked with them ever since.

The Uganda Child Cancer Foundation provides psychosocial support to children suffering from cancer which includes counseling, reading, writing, and painting. My mental health suffered as a child receiving cancer treatment. Living in the cancer ward, not everyone around you survives. I became depressed and I was only nine years old. Kids need a place to be themselves, to play and take their minds off treatment. The work of the Foundation is important to me because I know these children are getting support that I never received but would have benefitted from. Mental health and physical health go hand in hand.

As a Programs Director at the Foundation, I also help build awareness in high schools through the Children Caring about Cancer Project (3C’s Project). The 3C Project aims to empower young people with knowledge about cancer so we can reduce the late-stage presentation of cancer. We also fundraise to ensure families have funds to pay for their child’s cancer care, as treatment abandonment that often stems from financial difficulties is a leading reason for loss of children with cancer.

The onus is on us to create an environment of normalcy for PLWNCDs, where people understand that anyone can receive an NCD diagnosis, but that doesn’t change who they are, and you will not get the disease by associating with them. I fought cancer and won, and now I’m fighting the stigma that people with NCDs are doomed to die, because everyone deserves access to affordable NCD treatment. I hope others who have lived with cancer and other NCDs will feel empowered to share their stories to break down stigma and demand access to treatment for all.

*The Voices of NCDI Poverty Advocacy Fellowship provides those with lived experienced with NCDIs in the countries representing the poorest billion with mentorship, training in building successful advocacy campaigns, financial compensation, and the opportunity to take a voting role in the governance of the NCDI Poverty Network.