At ISPAD, PEN-Plus Puts Type 1 Diabetes ‘In the First Sentence’ of Care Delivery

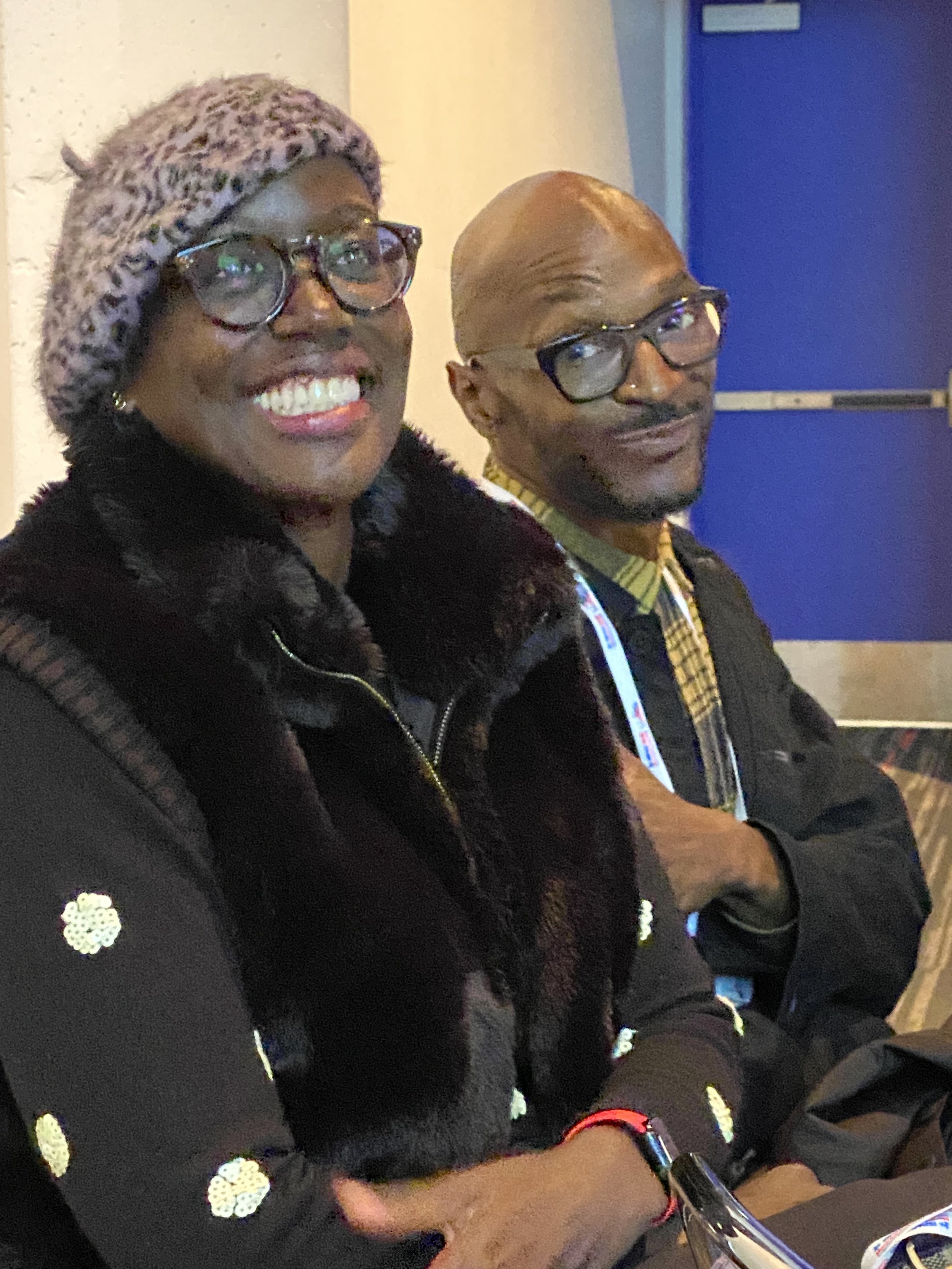

Sanjanaa Seshadri, advancement coordinator, and Mike Lawrence, communications manager—both members of the Boston co-secretariat of the NCDI Poverty Network—were on hand to talk about PEN-Plus during the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes annual conference, held this year in Montreal. (Photo: Rachel Gasana)

The PEN-Plus model of care is not only improving treatment and accessibility for people living with type 1 diabetes, but it’s also bringing new attention to the condition, Dr. Gene Bukhman said at a global diabetes conference earlier this month.

Speaking at the annual conference for the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, or ISPAD, Dr. Bukhman reminded audience members that in 2022, all 47 member states of the World Health Organization’s African Region set PEN-Plus “as their North Star” for the treatment of severe, chronic noncommunicable diseases.

“That’s incredible news for the type 1 diabetes community, because there’s actually a strategy in which type 1 is at the base of it,” said Dr. Bukhman, co-chair of the NCDI Poverty Network. “When people talk about PEN-Plus in Africa, when they talk about ministries launching their plan for PEN-Plus, they’re saying ‘type 1’ in the first sentence: ‘This is a strategy for type 1 diabetes, sickle cell, and rheumatic heart disease.’ That never happens for type 1.”

Or, at least, it hadn’t happened before PEN-Plus, a healthcare delivery model that emphasizes the integration of care for NCDs into the primary level of public health systems, bringing care closer to home for people in rural areas of low-resource settings who often have to travel far, to a tertiary-level hospital in a capital city, to access basic care and medicines for NCDs.

“PEN-Plus sits at an important nexus between tertiary centers, where you have pediatric endocrinologists, and then the community, and primary health care,” said Dr. Bukhman. “It’s also an amazing training platform to support people at lower-level health centers to provide care for more common conditions and, ultimately, to enable care for type 1 diabetes at primary health care facilities, which is where people would like to have care available.”

Dr. Gene Bukhman, co-chair of the NCDI Poverty Network, told a global audience at ISPAD 2025 in Montreal that the PEN-Plus model of care for noncommunicable diseases is building stronger health systems and improving care for type 1 diabetes through expanded training, resources and collaboration.

Equitable access to care was a key topic at this year’s ISPAD conference, which brought hundreds of leaders in the international pediatric diabetes community and related industries to Montreal in the first week of November. Dr. Bukhman’s comments came on the conference’s final day, during a panel providing international updates on care and resources for type 1 diabetes. The panel also included Dr. May Ng, a professor of child health at Edge Hill University and a consultant pediatric endocrinologist at Mersey West Lancashire Teaching Hospitals, in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Ng described how many Southeast Asian countries suffer from a severe lack of resources for type 1 diabetes care. She pointed out that Laos, a country of 8 million people, diagnosed its first type 1 diabetes patient only in 2016, and Myanmar, a country of 55 million, has just one pediatric endocrinologist.

“Children are dying in these countries because of a lack of expertise and lack of knowledge,” she said.

In his remarks, Dr. Bukhman—who is also executive director of the Center for Integration Science in Global Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, which serves as one of the Network’s two co-secretariats—said PEN-Plus was created because of gaps like those.

“Despite the work that so many have done over the years in many of these countries, when we started PEN-Plus operational planning processes in these countries, we found that there were still actually no type 1 diabetes guidelines in national systems,” Dr. Bukhman said. “There were no data elements in national systems. None of this was integrated into the public health system, despite the fantastic activities and the desire of diabetes associations in all these countries to have that. But there is a way in which PEN-Plus has unlocked that possibility. And it’s a real opportunity for all of us.”

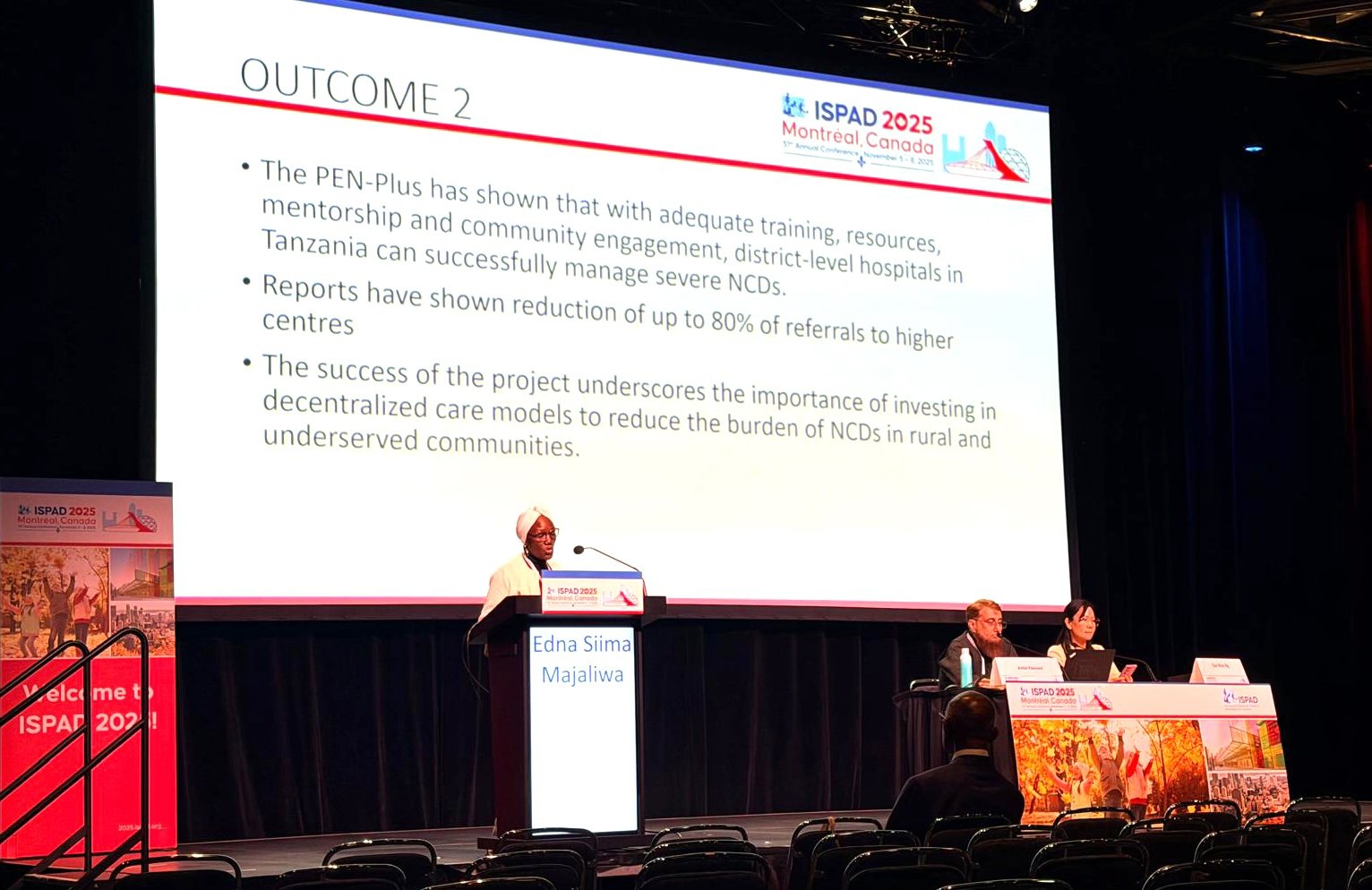

Edna Siima Majaliwa, a pediatric endocrinologist at Muhimbili National Hospital, discussed Tanzania’s experience with PEN-Plus during her ISPAD presentation, “Insights on Implementing Care Models in Varied Resource Settings.”

Dr. Bukhman said that since 2022, just after WHO African Region had approved PEN-Plus as its regional strategy, some “amazing milestones” have occurred for diabetes care in the region. He cited government support for PEN-Plus expansion in Malawi, Rwanda, and Zambia; the first two International Conferences on PEN-Plus in Africa, held in Tanzania in 2024 and in Nigeria in 2025; and last year’s launch of the Network’s five-year strategic plan.

“We’re starting to see national operational plans for expanding PEN-Plus implementation beyond a small number of training facilities,” Dr. Bukhman said, alluding to recent national plan launches in Zimbabwe and Zambia, and adding that eight more countries are expected to launch national plans early in 2026.

Dr. Bukhman said it takes more than policy, though, to transform care for NCDs, which often bring social challenges such as a lack of awareness, misconceptions, and stigmatization.

“What we’re talking about with integration is integration of social movements with integrated delivery models,” he said. “Those two things really have to come together in order to have progress in global health equity.”

Images from ISPAD

Clockwise from top left: Vivian Nabeta of the Sonia Nabeta Foundation and artist Kyle Banks, of Kyler Cares; global type 1 diabetes advocate Tinotenda Dzikiti; Dr. Apoorva Gomber, associate director of advocacy for the NCDI Poverty Network; Dr. Gomber and Emma Klatman, global policy and advocacy manager at Life for a Child; Dr. Elizabeth “Betty” Bankah, board chair for Diabetes Youth Care; and, from left, Dr. Gene Bukhman, co-chair of the NCDI Poverty Network; James Reid, type 1 diabetes program officer at The Helmsley Charitable Trust; and Rachel Gasana, senior director of advancement at the NCDI Poverty Network.